I had a stream of thought this afternoon – on the way Business Analyst’s think, and how that “way of thinking” can be applied to help define business problems. I thought I’d jot some of it down for my own future reference, and hopefully for the benefit of my readers.

I had a stream of thought this afternoon – on the way Business Analyst’s think, and how that “way of thinking” can be applied to help define business problems. I thought I’d jot some of it down for my own future reference, and hopefully for the benefit of my readers.

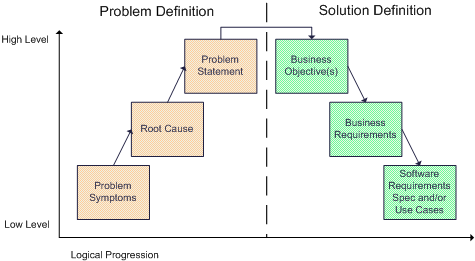

Successful business analysts have an ability to draw ideas to their logical conclusions. An analyst’s work typically requires assessment of concepts following a progression from the general to the specific, and other times from specific to general.

Progression from the general to the specific is what Business Analysts are most known for. This is where we take a high-level business problem and objectives and decompose them into requirements that represent functions and attributes of a system or solution. Nearly every job posting you’ll see for a Business Analyst will mention this need to be able to elicit requirements and produce the accompanying documentation.

Less widely acknowledged – although equally important, in my opinion – is the progression of rolling up symptoms and side effects of business problems into higher-level root causes and problem statements.

Here’s a simple illustration of a logical thought progression during business analysis:

And the point is..?

It’s not rare that I hear about a business owner who has heard about a problem or defect or two and, based on a few scraps of information, is ready to dive head-first into solution details. More often than not, this approach will lead to a solution that addresses symptoms while leaving the larger, fundamental problem undiagnosed and unfixed.

Organizations seem to have a tendency to skimp on root cause analysis. It can be a wearisome job requiring time and intensive research. However, if we haven’t done due diligence to identify and solidify root causes of business problems, how can we have a level of confidence that our solutions are fixing them? I think this is where the BA can really add value outside the traditional “writing up specs” role.

If a BA can get involved with the business decision makers early enough and help ensure that symptoms are traced to their true causes (which, incidentally, often turn out to be the causes of multiple other symptoms) and the business problem is succinctly defined, then a project has a much better chance of successfully solving the business problem.

Summary & Conclusion

- Business Analysts are skilled in tracing problems and ideas to their logical conclusions; from specific to general and from general to specific.

- Business stakeholders often mistake symptoms for business problems because they don’t do sufficient root cause analysis.

- Business Analysis skills can and should be leveraged to help define business problems.

- Projects are more effective when they address real business problems and not just symptoms.

Wouldn’t we all rather be involved in projects that we know will effectively solve business problems?

Alright, thinking about thought is tiresome, so I’m going to put down the virtual pen for now. What are your thoughts on the topic?

Spot on, Jonathan. At my place, however, time and time again I see the same two problems getting in the way of our ability to effectively solve business problems:

1. Business analysts don’t get involved early enough. Other ‘roles’ in the organisation, who do have early contact, prematurely propose potential solutions to our customers.

2. Customers don’t see value from taking time to think and analyse. They want quick answers and then get into the solution domain as quickly as possible.

In some respects these are cultural issues. I suspect though that my place is not unusual in this respect!

Yes. I have worked in organisaiotns where great effort is taken to understand the problem before picking a solution, but also in places that only addres the symptoms.

Good anlysis only goes so far though. Good executio is equally important – to the degree that a good solution executed on a symptom can usually be better than a poor execution of a solution to root cause problems.

Hello, I am a student and currently doing Bachelors on Business Administration. You have described beautifully what a business analyst is, what knowledge and expertise he/she must have etc. I would like to add add an important thing into this post that a business analyst must have a complete knowledge of current business-market situation. Because every business depends upon market situation. In short, a good business analyst must be a good market analyst too.

I would also like to thank you for such a informative post. It would surely me in my studies. So thanks a lot. I would like to visit your website again for more readings.

No problem, Alex.

Yeah, the community portal-type stuff and wiki are exciting possibilities. I think we'll find that there are plenty who are willing to step up and help organize and contribute.

By the way, I've been checking in at http://businessanalystmentor.com periodically, and you've really got the site looking good. Nice work!

Great work! Thanks for sharing!

Great Post Jonathan! Still relevant 4 years on..

The problem that I find in my current role as a newbie in the BA field is that I’m being asked to write a functional specification, based on sparse business requirements, and virtually no problem statement.. Is this a common BA experience!

Thanks for commenting, Jay. I find that posts about tools and the hot methodology of the day tend to have a shelf life, but the fundamentals do seem to stand the test of time.

The situation you describe is, I’m afraid, very common. The best way I’ve found to address it, though, is not to settle. If you’re going to do quality work and put your team in a position to succeed, you’ve got to have a solid understanding of the problem and objectives.

It’ll be your job to elicit that problem statement and business requirements. You might need to talk to several people and do some research to piece together the puzzle, but not doing it is too risky.

What you find is that sometimes when the business stakeholder(s) don’t provide you with a foundational problem statement and objectives, it’s because they don’t even really have a solid understanding of what they need themselves.

There are a couple “pet questions” that I often start with to get discussion with my stakeholders moving on the topic of problems and objectives, and they might serve you well:

1: What point(s) of pain caused you to request this project? Of all the things our people could be working on, why should we focus on this request? What would we risk by not doing this project?

2: What does success look like to you? Imagine we have completed the work, and all has gone according to plan. What is better now? What are we able to do that we couldn’t before? How have we improved the business?

Last of all, remember that as a Business Analyst, your job is not to invent requirements, or author them – you elicit them from stakeholders. For a project effort to be successful, you have to have access to the people who can give you the information you need.

Great post and great questions are below too. Don’t missed them.

Jonathon,

how much analytical do you have to be to become a business analyst? I am good with people and also good with writing documentation. i have a business degree. The thing that scares me is that…i am not super analytical…more of like creative type. I was wondering if business analyst would be a good choice for me to go for if you are kind of creative?