In Requirements, Accuracy Isn’t Enough

Allow me to reflect and maybe even toot my own horn here for just a second. Since I’ve been a business analyst, I think it’s fair to say that I’ve written accurate requirements. By this I mean that they have accurately represented what a user needed to be able to do, and what the system needed to be able to do to meet the business requirements. Despite my presumed accuracy, I’ve faced projects where there has seemed to be an inordinate amount of churn around the wording and language used in expressing requirements – sometimes to seemingly annoyingly inane levels (“Hmmm… That all depends on what the meaning of ‘is’ is….”). Especially as a younger BA, I couldn’t understand why the designers and testers couldn’t understand plain English and just do what the requirements said.

Well, years and experience have tempered me somewhat, and although I still have room for improvement in a lot of areas, one concept has helped me improve a great deal as a business analyst. It has also helped me to understand the angst of the QA analyst and design architect. Today, I’d like to pass it on to those who may benefit from the same lesson. That is:

It’s not enough for requirements to be accurate, they must also be precise.

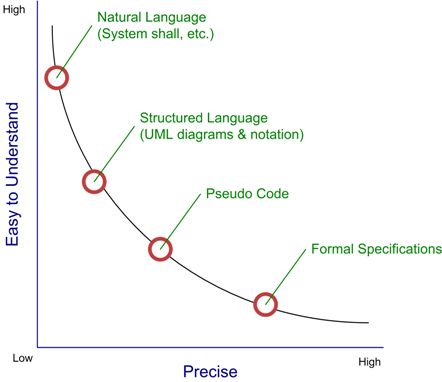

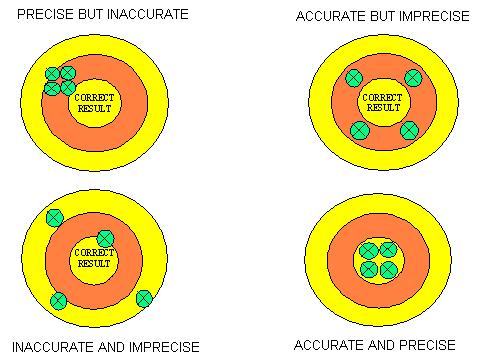

What is the difference, you ask? Have a look at the image below.

Image above originally sourced from Alcontrol.co.uk.

Accuracy, as you can see on the examples on the right side of the image above, is hitting close to the target. Precision, as evidenced in the top left and lower right examples, is consistently hitting close to the same spot. Obviously, both are important, and the good BA must strive for requirements that are accurate and precise.

So, while I was writing accurate requirements, I was only meeting half of my obligation to downstream delivery teams. To be a good business analyst, I need to communicate in terms that are not only accurate but clear and consistent.

Natural language is inherently ambiguous

The odds are stacked against the BA when it comes to writing requirements that are both accurate and precise, as natural language is inherently ambiguous. The same phrase, punctuated or intoned differently can take on a variety of meanings. For example,

“I, John Doe, am glad to see you here!”

Am I John Doe, and telling someone ( or maybe even a group of people) that I am happy to see him (/her/them) here, or am I addressing myself to John Doe and telling him I am glad to see him here? The statement is accurate, and both are are valid interpretations of the sentence, but only one is the correct result. This is an example of the difficulty I was experiencing with my “accurate requirements”. Different people can understand the same phrase differently depending on the individual and the context. So, how does a BA cope with this?

Some shops adopt different, more precise ways of expressing requirements such as UML, pseudo code, and formal specification language. Here are a few examples of alternatives and how they compare to natural language requirements:

- Natural Language which includes your typical “user shall” or “system shall” requirements. These are considered the most “understandable” because natural language is the language in which we speak and write. In theory, anyone who can read the language should be able to understand what the requirements are saying. For example, a business stakeholder who has no technology experience, and doesn’t care to bother learning UML or more precise forms of specification will prefer natural language requirements. In my experience, we pretty much always write up our business requirements in this way – be it just a list including vision and objectives, a few user stories, or whatever the case may be. As we mentioned before, natural language is the most open to multiple interpretations and hence the least precise method.

- Structured Languages like UML that represent natural language through the use of graphics and rules within a structure where each element has a distinct meaning. The symbols and notation rules in UML allow for it to be a more precise means of expressing requirements. UML is still relatively easy to understand, but not as easy as natural language as it does require a little bit of study or training to understand the ins-and-outs. UML diagrams – especially activity diagrams and use case diagrams – are a great alternative to natural language as a way of expressing user and functional requirements.

- Pseudo Code, or more descriptive languages include if/then/else and other logical statements that read as much like code as they do natural language. It doesn’t necessarily resemble any one particular programming language, but uses common syntax and attributes that allow it to be flexible across technologies. Again, the rules, conventions, and structure of this type of method makes it very precise, although very difficult to read for those that aren’t familiar with the language and logic of software development. Detailed system and design specs are most likely to include this type of language.

- Formal specification language goes a step beyond pseudo code to include mathematical logic and a code-like format. I’ve never been in an environment that uses this type of specification, but I’ve been told that it is common in aerospace and weapons technology – where lives are at stake, and precision is of the utmost importance – and the user group is familiar with the technical terminology. If you’re curious, here is a link to a page that describes some of the syntax of formal specification language below. Wikipedia also has a worthwhile entry. This link describes the different types of formal specification languages. I’ll also give an example just to emphasize the low-understandability aspect.

Delete(Insert(s, e), e’) ==

if e=e’

then Delete(s, e’)

else Insert(Delete(s, e’), e);

How do I write accurate and precise requirements?

This post is addressed chiefly to the good, old natural language requirement writer, though. Given that natural language is the least precise method of expressing requirements, and given that we need to increase the precision of our requirements for them to be of good quality and use to their consumers, what do we do?

We make our requirements reliable. We make them consistent in form and structure. We adopt a limited, well-understood vocabulary and stick to it. We make our requirements “boring”. This allows us to ensure that each arrow (requirement) is hitting very close to the last. It gives us precision in addition to our accuracy. I have some ideas on how to standardize requirements and make them more consistent and precise, but I’m getting a little long-winded here, so I think I’ll share those in a different entry.

My main point here, and I hope I’ve been able express it adequately, is that the business analyst’s job is not complete if the requirements are written and accurate but not precise. The key is to find a way of articulating requirements that is as precise and as easy to read by the target audience as possible. I’ve found that as my requirements become more precise, the churn around language and semantics decreases significantly. I suspect that many BA’s may find the same to be true.

Anyway, look for follow-on posts in the coming days that will address requirement structure, requirement vocabulary, and any other tricks of the trade I’ve picked up that I think worthwhile to pass along.

In the meantime, take a quick look back at the image detailing accuracy vs. precision. I found it interesting to briefly contemplate the ways that writing precise but not accurate, or accurate but not precise requirements could impact a project.

As always, I’ll be glad for any comments or experiences that you may have had in dealing with issues of accuracy and/or precision in your requirements.

Consider two additional factors to this conversation.

First, the lean, agile development movement presents complexities (and perhaps frustrations) for business analysts.

Code iterations are inherently high precision (in terms of requirements accuracy, in so far as considering code as the ultimate in requirement statement). Since the client can see them execute, they are easy to understand as representations of requirements as well.

On that theme, visualizations are also very understandable, and very precise. By visualizations I mean anything from story boards to flash demos up to code demos. At some point, the visualization overlaps with an actual iteration.

Second, this understandability vs precision doesn’t deal with the elephant in the room: the accuracy of the requirement. I know, that’s not the topic of this diagram nor this conversation – but it is a vital topic. How likely is it that the requirement statement actually matches the code that ultimately is delivered?

I’ve built a revision of your ease vs precision diagram, to show these two factors with the additional accuracy axis. You can see it (and of course comment) at http://outside-in-thinking.com/?p=63

This is an interesting article. I like the perspective you advance, and I look forward to reading your follow-up to this.

I really enjoyed reading your article and looking at the problems when dealing with language. You really take the requirement engineering one step deeper with this analysis. In measurements your diagram of accurate and inaccurate, imprecise and precise is the exactly the same as random and systematic errors. It is interesting to note that measurement is a language bound by rules as with requirements engineering. Where random errors can be reduced with averaging, and systematic errors can be reduced with calibration. The main issue with measurements and as well as requirements engineering is the fact that you cant get the perfect measurement unless you could take an infinite number of samples. This seems to parallel in that you can cannot describe a perfect requirement unless you describe it an infinite number of times. As you see without getting into to much detail, the point I am making is that problems with systems development are the same problems as with measurement.

Brad, I believe the argument for perfection as the problem is what prevents us from advancing the practice of software development. If the position being advanced doesn’t achieve perfection, we end up doing the same old tired practices that we know require improvement. The search for perfection is the enemy of good software development practices being adopted. Better practices don’t need to advance the art to the level of perfection to improve our success.

Carl – Thanks for stopping by, and for the great comment. I tried to register to post a comment to your blog, but had a bit of trouble. I’ll try again later today.

I like your revisions to the diagram – especially the addition of visualizations and code iterations and the “accuracy with final product” dimension. That’s great stuff.

I can also appreciate your notion that if the code iterations commonly used in an agile environment are the most accurate, precise and understandable way of expressing requirements, then the BA does face some challenges in that environment inasmuch as he/she is probably not best suited to produce these types of “requirements.”

I haven’t worked in a purely agile/lean development environment but am interested in learning its merits and shortcomings. Perusing your blog has also got me very interested in Outside-in Software Development.

Brad –

Spoken like a true engineer!

Thanks for visiting and for chiming in. I can’t speak with any great level of expertise on formal principles of measurement, but agree that the parallels are there; certainly that there are at least principles – if not rules – to writing requirements that help reduce requirement “errors.”

Welcome back, Bill.

Your comment reminds me of the quote/maxim:

Question: “How do you eat an elephant?”

Answer: “One bite at a time!”

I agree that we too often see or hear of the all-or-nothing or “silver bullet” approach to improving processes and performance.

Unfortunately, there is no silver bullet. Fortunately, incremental improvement – through means as small as uniformity of requirement structure – can make a big difference over time.

This is a great conversation and one that Alistair Cockburn has written about as well. It seems that Jonathan and Alistair are heading in the same direction. Here’s a link to Alistairs article:

http://alistair.cockburn.us/index.php/Parts:_precision%2C_accuracy%2C_relevance%2C_tolerance%2C_scale_in_object_design

Thanks for sharing the link, Keith. I’ve casually perused Cockburn’s site a few times, but had never come across that entry. Good stuff.

By the way, I really enjoyed your presentation at the Atlanta IIBA meeting a couple weeks back, and I’ll be tracking the webcasts on requirements.net as well.

Thank you for your article about the fascinating world of requirements in natural language.

You may be interested in a report from NASA, that evaluates six tools, that analyze requirements written in a natural language. They spent a year evaluating these tools, using criteria like completeness,consistency, precision, etc.

The report is avaliable. Mail to:

valerie.s.jones@ivvv.nasa.gov

Herman,

Thanks for visiting my blog and taking a minute to comment. I hadn’t heard of that report and would certainly be interested. Thanks for the tip!

Jonathan,__It feels a bit that the confrontation between easy to understand and level of detail is a dilemma! But there is off course a possibility to use the path natural language – structured language – pseudocode – formal specification language. The growth in level of detail and the accompanied shrinking level of understanding is related to who reeds the requirements. A business manager wants natural language, ICT can use pseudo and formal. In several companies where i worked i saw your path "live" and i experienced i can use this path because the more level of detail you put in requirements, the more "techical" the audience is! Take your 4 stages and level them to Business requirements, functional requirements, user requirements and system requirements. Your path is not a problem, it is a chance and that seems te me the way to cope with it.

Appreciate the comment, Wilco! And you're right, I think finding the right type of "language" given the situation and audience can be a dilemma.

We definitely want the requirements to be accurate, and we definitely want them to be precise, but not to the extent that they aren't readable to the target audience.

Equating the different types of language the the requirement types is an interesting approach.